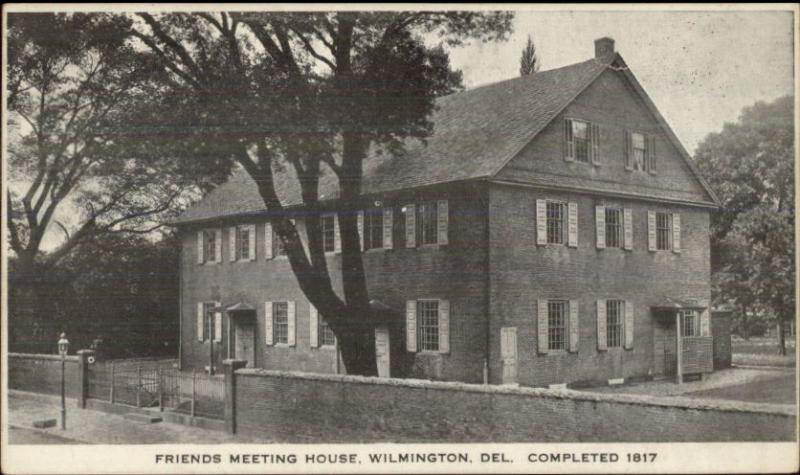

Wilmington Friends Meeting House

Place Details

- [email protected]

- Phone

- 302.652.4491

- Address

- 401 North West Stret,

Wilmington, DE 19801 - Parking

- On-street Parking

- Place Type

Description

Since 1738 the Wilmington Monthly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends has been a presence on the high point of land between Fourth and West and Washington Streets. Its three successive Meeting houses have escalated in size from the first building measuring 25’ by 25’ to the present one designed in 1817 to accommodate a membership of 120 families, representing 700 individuals. The Meeting now has approximately 400 members. The burial ground, last resting place of the famous “penman of the Revolution,” John Dickinson, contains also unmarked graves of the town’s many victims of the yellow fever epidemics of 1719 and 1802 as well as graves of Meeting members, the low headstones uniformly modest in size in accordance with Friends belief in simplicity.

In accordance with Quaker dedication to the education of children, a school was held in that first small Meeting house. Here Wilmington Friends School had its beginning in 1748 and, with many sprawling additions to the building and a growing enrollment, remained on Quaker Hill in continuous operation until 1937. At that time the size of the student body and the limited space in the old building made it advisable to move the school to the outskirts of Wilmington, in Alapocas. After remodeling and a few years as an apartment building, most of the old school was torn down, including the last bricks of the 1738 Meeting house.

The first recorded Quaker meeting for worship in Delaware was held in New Castle in September 1672. George Fox, English founder of Quakerism, visiting in America, came to New Castle where, according to his Journal, Governor Lovelace offered his house for a meeting – a “pretty large one; for most of the town were at it.” Many early settlers came to America from England and Ireland seeking religious freedom in William Penn’s Three Lower Counties on the Delaware. Small groups of Friends worshipped in members’ homes and soon Newark, Centre and New Castle Meetings were formed. The Brandywine “a desperate river hazardous to us and our horses” and the Christina Rivers made communication difficult between the Meetings, particularly in winter, for the first bridge across the Brandywine was not built until 1762.

By 1735 Willingtown consisted of 15 or 20 houses clustered near the Christina River. In May of that year William and Elizabeth Shipley, Quakers from Ridley Township in Pennsylvania, came to Willingtown and built a one-story brick house near Fourth and Shipley Streets. The first Friends meeting for worship in Wilmington was held in the house. From that small group of worshippers, Wilmington Meeting, as a religious body, evolved. First established as a Preparative Meeting, the status of Monthly Meeting was finally allowed by the Concord Quarterly Meeting in 1750. Wilmington Meeting is now a member of Concord Quarterly Meeting and of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting.

In 1738 on land given by William Shipley, the first Meeting house was built on Quaker Hill at the corner of High Street (now Fourth) and Sassafras (now West). This small building was soon outgrown and a second place of worship was erected in 1748 on the west corner of the two streets, large enough for a congregation of 500 persons. As the number of Friends grew a still larger Meeting house became necessary and on September 25, 1817, the present building was opened for worship and the earlier one razed. Since that time interior changes have been made to accommodate the First Day School, to provide kitchen and bathroom facilities, and to install central heating. The great paneled partition in two parts that once rose from the basement and descended from the attic is now inoperable. In 1951 an addition was attached to the rear of the building and designed to conform as nearly as possible to the style of the Meeting house. This additional space provides for social events, meetings, and First Day School classes.

The neighborhood surrounding the Meeting house has witnessed many changes over three centuries from an open country hilltop to solid rows of city houses. In the late 18th and early 19th century Friends families lived near the Meeting house, but succeeding generations of those families tended to move to suburban areas. Now, gracious historic brick homes built in the 19th century and more modern twentieth century homes face the Meeting property. The old burial ground with its tall trees, smooth lawn, and flower beds continues to provide a green oasis on Quaker Hill. The Meeting cherishes its place in the community, and as it always had, welcomes neighbors from near and far to share in Friends’ worship.

[Excerpted from a pamphlet written by Anne P. Blake]

Delaware’s Greatest Stationmaster on the Underground Railroad

Perhaps unequaled in American history is the powerful impact that the Underground Railroad and its seemingly ordinary citizens working as conductors and masters, had in changing society. In Delaware, a few very effective abolitionists worked for many years sending fugitive slaves along the road to freedom. There were Underground Railroad stations throughout the state…in Blackbird, Camden, Middletown, New Castle, Hockessin and Wilmington.

As a border state, Delaware had citizens who felt strongly both for and against slavery. But, in spite of strong opposition, men like Isaac Flint, John Hunn, Joseph Walker, and Thomas Garrett worked to provide a safe journey for the slaves they met. It is difficult to imagine the courage, determination, strength, ingenuity and fear that the station masters, conductors and fleeing slaves faced as the Underground Railroad performed its miracles.

Thomas Garrett (1789-1871), who lived at 227 Shipley Street in Wilmington, was Delaware’s greatest station master. He is credited with helping 2,700 slaves reach freedom. A brave, big-hearted man, he opened his heart and home each time he was called upon. Garrett lived his Quaker faith and its main precept that God resides within a person’s soul, leading him in his work.

Thomas Garrett (1789-1871), who lived at 227 Shipley Street in Wilmington, was Delaware’s greatest station master. He is credited with helping 2,700 slaves reach freedom. A brave, big-hearted man, he opened his heart and home each time he was called upon. Garrett lived his Quaker faith and its main precept that God resides within a person’s soul, leading him in his work.

Beginning near the end of the 1820’s, Garrett devoted most of his lifetime to the Underground Railroad, serving until 1864. Except when threatened by police capture, Garrett worked “without concealment and without compromise.” Because of this, his reputation spread quickly among both slaves and whites.

With increasing numbers of slaves coming to him, by the late 1830’s he could no longer accommodate everyone and enlisted several local assistants. He also found outside sources of financial support. Many of the fugitives he saw needed clothing, shoes, money for transportation and help getting started.

Garrett helped as he was able. On one occasion Harriet Tubman, who had become a close friend, asked him directly for nearly $25 for slaves she was leading. Garrett replied by asking how she thought he could possibly supply her with such a large sum. Tubman replied that God had sent her to him. Garrett could only respond that indeed He had, having just returned from the bank where he had converted an English 5 pound note (a gift) into $25! Groups from as far away as Edinburgh, Scotland sent gifts for Garrett’s cause.

Not everything went as smoothly for Garrett. In 1848 at the age of 60, he and John Hunn from Middletown were brought to trial for aiding fugitive slaves. Both men were found guilty and fined severely. Garrett was forced to sell his iron and hardware business along with his personal property at auction to pay the fine. Friends purchased Garrett’s property, allowing him to use it and buy it back when he could.

In 1850 the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, intending to deter slaves from attempting to escape as well as anyone who wanted to help them. Although it was more dangerous, the Underground Railroad continued, becoming more successful. By the end of 1857, Garrett had helped a total of 2,152 slaves.

In January 1871, an estimated 1,500 people overflowed the Wilmington Meeting House at Fourth and West Streets awaiting the arrival of several young black men. These men carried Garrett’s last remains on their shoulders, up the steep hill from his house on Shipley Street. The inspiring voice of abolitionist Lucretia Mott, another well-known Quaker, rang out over the wooden benches of the Meeting House in praise of the man they all came to know as “unrelenting” in his willingness to help the runaway slave. Those who heard her wept. It was called “the most moving funeral in the history of Wilmington.”

[By Ellen Peterson, with Jim McGowan; reprinted with permission from the Harriet Tubman Historical Society]