By John Medkeff, Jr.

The return of Wilmington Beer Week, the celebration of beer downtown and throughout Greater Wilmington, presents the perfect opportunity to look back at the area’s deep and storied history with the sudsy beverage. Few areas in the country have as long a relationship with beer as Northern Delaware. Today, Wilmington’s three breweries and the 15 others in the metro area from Claymont to Middletown are resurrecting a brewing tradition that extends all the way back to the 1630s and the first Europeans to settle in the area.

Beer may be a tasty social lubricant these days but for Delaware’s early Swedes, Finns, Dutch, English, and others from the Continent, the drink was an integral part of their daily diets. Back in their native lands, water sources were often polluted and not safe to consume, particularly in villages with sizable populations. They didn’t yet understand that boiling during the brewing process killed harmful bacteria in the water. Naturally, they associated beer with good health, and it was the drink of choice for most men, women, and even children.

Beer was so important to the early Swedes and Finns, that one of the first activities they planned upon arriving in Wilmington in the spring of 1638 was planting the seed to grow wheat and barley for baking and brewing. They built the first proper brewery at Fort Christina years before dedicating their first church. The earliest documented record of brewing at the fort was a special brew unveiled for the Christmas celebration of 1654. The Swedes had big plans for brewing, hop growing, and malting in the colony, but those plans would never come to fruition. Brewing operations at the fort were always as meager as the colony’s population, and the Swedes would soon be supplanted by the Dutch.

During the 1655 invasion of Fort Christina by Peter Stuyvesant’s legion of soldiers, Swedish Governor Risingh vowed to defend the fort until the last barrel of beer was finished. He and his small band of men were no match for the Dutch. The most prized possession captured during the raid was the Swede’s brew kettle. Stuyvesant shipped the kettle southward to Fort Casimir at present day New Castle, where he had his own brewery installed.

The Dutch had an even more significant relationship with beer than their Nordic counterparts. Back in Holland, beer had been a significant commodity they produced and traded for more than a century. In fact, at the time of their invasion of the Swedes, brewing was already a growing trade in Dutch settlements in New York. During their decade-long reign along the Delaware, the brewery at Fort Casimir and two in the surrounding village were pumping out beer for local taverns.

While beer was no less important to the English, larger-scale beer production seems to have taken a back seat during their early rule in the late seventeenth century, at least as far as the Delaware region is concerned. William Penn left Delaware high and dry, choosing instead to build a brewery at his estate just north of Philadelphia. Nevertheless, the English established a circuit of taverns in towns and along key roads in the new colony, which served as important community centers and travel stations. Lacking nearby breweries, the women and men who operated the taverns in the Delaware colony had little choice but to brew their own ale for patrons.

At long last, in the late 1720s, Wilmington would have its day. William Shipley, the virtual founder and eventual first burgess (mayor) of the city, came from Darby, Pennsylvania to the struggling village of Willingtown with big business plans. One of Shipley’s earliest ventures was a malt house and brewery, which he built on the northwest corner of Fourth and Tatnall streets. During the Revolutionary War, when brewing ingredients were in short supply, the brewery was a significant supplier of malt to Philadelphia brewers. The enterprise passed through several Shipley heirs and then a series of other proprietors before closing around 1830. It remains the longest-operating brewery in state history.

The Shipley brewery’s chief competitor from the 1770s through the early 1800s was located only two blocks southwest along Second Street, between Tatnall and Orange, and owned by the Sheward family. Caleb Sheward was an experienced Quaker brewer, who, like the elder Shipley, came to Wilmington from nearby Pennsylvania. Unlike the Shipley’s descendants, Sheward considered himself an Englishman and was loyal to the Crown. Local authorities busted Sheward for selling ale to the Redcoats during their occupation of Wilmington. Still, Sheward’s brewery thrived as it passed through several heirs before finally running out of steam in the early 1840s.

Beer had fallen somewhat out of favor by the early 1800s in Delaware and across the young country. The drinking public became enamored with more spirituous beverages like whiskey, rum, and brandy, which were more portable, less subject to spoilage, and provided a bigger buzz for the buck. The resulting social ills created by an increasingly drunker population led to the beginning of the Temperance movement in the early part of the nineteenth century. By 1847, drunkenness became such a problem that Delaware passed statewide prohibition, but the regulation was quickly declared unconstitutional.

A less intoxicating, more effervescent and refreshing beverage would arrive in Wilmington in 1850 and soon take the city by storm. That year, Bavarian immigrant brewer Christian Krauch came to the burgeoning city and set up a hotel and saloon on lower King Street. Krauch had been brewing for years in Philadelphia when yeast that made lager beer possible arrived in that city from Germany. He brought some of the magic yeast with him down to Wilmington and began brewing lager in a small kitchen brewery behind his saloon. Krauch’s lager proved popular in a town teaming with thirsty immigrant workers. Though brewing was never a large commercial enterprise for Krauch, he inspired Wilmington’s next generation of brewers. Those men would on to much bigger things and usher in the golden age of brewing in the city.

John Fehrenbach, who served a stint as Krauch’s bartender, opened his own saloon and, like his mentor, began brewing lager beer for his patrons. At the close of the Civil War, Fehrenbach entered into a partnership with his brother-in-law, John Hartmann. The two purchased the property in the Forty Acres at Lovering Avenue and Scott Street and built a sizable brewery, hotel, and saloon. The brewery expanded greatly as demand for H&F’s lager continued to grow. After the deaths of the founders in the 1880s, ownership passed to their sons, who enlarged the brewery. H&F kept pumping out their popular lager and porter until National Prohibition and the deaths of the owners brought the business to a close. H&F’s hotel and saloon, once part of the brewery complex, survives to this day as Gallucio’s Italian Restaurant.

In the latter half of the 1800s, lager’s incredible popularity elevated beer brewing from a vocation or side hustle to a legitimate, if not extremely profitable, profession. By 1900, brewing was the sixth largest industry in Delaware. H&F and two other large Wilmington beer producers accounted for nearly all the state’s beer production before 1920.

Another Krauch acolyte and former Wilmington neighbor, Joseph Stoeckle, started brewing in the back of his King Street saloon in the late 1850s. After the failure of the Nebeker brothers’ brewery at Fifth and Adams streets in the 1860s, Stoeckle became involved with a group of investors in a new organization.

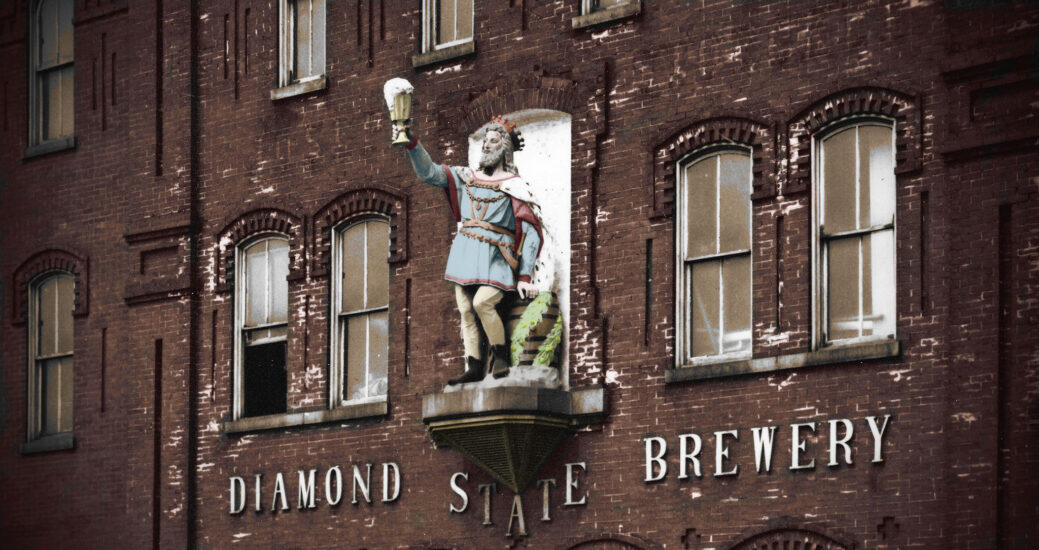

In 1872, Stoeckle assumed complete ownership of the brewery, renaming it the Diamond State Brewery. A fire levelled the brewery in 1881, but Stoeckle rebuilt a substantially larger brick complex, which was adorned with an 11-foot statue of the legendary European king of beer, Gambrinus.

Under Stoeckle and his son Harry’s expert management, the Diamond State Brewery would overtake H&F as the city’s largest beer producer. The brewery’s Select Lager became so popular that the Stoeckle name would be synonymous with beer in Wilmington for decades to come.

Eight blocks due west of the Diamond State brewery, at Fifth and DuPont streets, was the third of Wilmington’s Big Three lager breweries. Known most commonly by old residents of the city as the Bavarian Brewery, ownership passed between three principal operators from the 1880s through the early 1900s. After the death of his father, Herman Eisenmenger was largely responsible for the phenomenal growth of the Bavarian Brewery. The brewery sales never trailed far behind Stoeckle or H&F.

Wilmington had a host of other smaller breweries from the post-Civil War period through the early 1900s. The most notable was the Wilmington Brewing Company in the 200 block of French Street. The brewery was owned by Joseph Stoeckle’s son-in-law, Henry Blouth. The competition naturally caused consternation among Stoeckle family members. The brewery’s decade-long run ended with Blouth’s sudden death in 1913. His wife shut down the brewery and sold the equipment to her brother, Harry Stoeckle.

Beer remained very much a local product in the Wilmington area. The city’s Big Three breweries had large stakes in or outright owned many of the outlets of distribution, including saloons, hotels, restaurants, retail outlets, and bottling plants. Stoeckle, H&F, and Bavarian had a virtual stranglehold on the beer market from Seaford to Claymont.

Fueled by rapid industrialization and waves of immigration from beer-loving countries, Wilmington in the late 1800s was a growing city with a big thirst for beer. And drinkers had plenty of places to find their favorite beverage. By 1890, there were more than 180 drinking establishments and outlets within Wilmington’s city limits.

Alas, Wilmington became a drinking city with a working problem. Drinking had gotten out of control. The most notorious strip was between Water and Front from Walnut to Justison streets in an area known as The Coast. Mixed among more respectable establishments were seedy gin mills, gambling dens, after-hour dance halls, and brothels. These were places where a man could easily lose an entire paycheck or far worse. Even Wilmington’s police force was hesitant to patrol the area, preferring instead to deal with the aftermath.

In response to the chaos caused by rampant overindulgence, the Temperance movement steadily gained traction in the first decade of the 1900s. As public protest turned to legislative action, the focus of Dry advocates advanced from pleas for moderation to outright prohibition. By 1917, the sale and distribution of beer were prohibited throughout Delaware, except in the city of Wilmington.

National Prohibition in 1920 ended legal beer production at the Stoeckle, H&F, and Bavarian breweries and caused irreparable damage to the businesses. The Big Three tried to make a go of it in the early 1920s producing soft drinks and near beer. Ultimately, all three found it impossible to cover the costs of operating such large plants, especially during the challenging economic times of the Great Depression. Stoeckle and H&F went out of business by the middle of the decade.

Tough times called for desperate measures, and Herman Eisenmenger turned to less than legal means to keep his Bavarian Brewery afloat. He began making full-strength beer for mob distribution. The feds busted up the operation in 1927, and the brewery was shuttered.

When national Prohibition regulations were repealed in 1933, two of Wilmington’s breweries were preparing for production. Though not particularly well-funded, Eisenmenger managed to retool his old brewery and get it back online. Unfortunately, the implementation of the three-tier liquor distribution system opened Wilmington to competition from larger and better-resourced national and regional brewing corporations in the East and Midwest. Eisenmenger’s Bavarian-Luxburger Brewing Company lasted only a year and a half.

The Delmarva Brewing Company occupied the brewery from 1938 until 1944. They were subject to the same competitive pressures as their predecessors and encountered shortages of ingredients and materials caused by World War II.

The Bavarian brewery’s final occupant starting in 1944 was the Krueger Brewing Company of Newark, New Jersey. In 1935, Krueger became the first brewery in the world to sell canned beer. While they intended to use the Wilmington brewery to expand their reach southward, the experiment proved to be an abject failure. Krueger moved out in 1951, and the brewery would never again open. The complex was torn down in the 1960s and replaced with public housing.

A more successful and longer-lasting brewing company, the aptly named Diamond State Brewery Inc., purchased the old Stoeckle plant and opened for business in 1936. The brewery had a good run through the war years and into the mid-1950s. Eventually, Diamond State fell victim to fierce competition from much larger breweries outside the region. The last of Wilmington’s Big Three breweries closed in 1954 and, in the early 1960s, was demolished to make way for I-95 through the city.

By the 1990s, interest in locally sourced and nearly forgotten beer styles took hold in Delaware. The first brewery in the city in 40 years, the Rockford Brewing Company, opened in 1995 at St. James Court, on the south edge of the city line. The brewery was beleaguered by production and distribution issues and lasted only three years.

A series of brewpubs had short runs in and around the city in the 1990s and the first decade of the new millennium, including Downtown Brewing Company, John Harvard’s Brewhouse on Concord Pike, and the Brandywine Brewing Company of Greenville.

Just down Kennett Pike, Twin Lakes Brewing Company opened a small production on co-owner Samuel Hobbs’ scenic historic farm in 2006. Their Greenville Pale Ale was one of the area’s most popular beers for many years. Sadly, the brewery changed hands in 2016, made an unsuccessful move to Newport, and closed in 2020.

To the satisfaction of Wilmington beer lovers, recent history has shown far more brewing successes than failures. The city’s new Big Three Breweries — Iron Hill Brewery, Wilmington Brew Works, and Stitch House Brewery — and their 15 counterparts in New Castle County continue to build on the area’s nearly four-century-long brewing tradition and bring good cheer to the region. We do indeed have a rich past and present to celebrate this Wilmington Beer Week.

A Campaign Fit for a King

“Restore the King,” a publicly-funded campaign to repair Wilmington’s historic King Gambrinus statue, is well underway. The 140-year-old sculpture of the king of beer was an icon of the city for generations. Its restoration symbolizes the return of beer as a significant economic, cultural, and social driver in Delaware. Once restored, the statue will be donated to the Delaware History Museum for public presentation and long-term conservation.

“Restore the King,” a publicly-funded campaign to repair Wilmington’s historic King Gambrinus statue, is well underway. The 140-year-old sculpture of the king of beer was an icon of the city for generations. Its restoration symbolizes the return of beer as a significant economic, cultural, and social driver in Delaware. Once restored, the statue will be donated to the Delaware History Museum for public presentation and long-term conservation.

Visit RestoreTheKing.com to learn more about the project and donate to the cause.